Off the Shelf #6

The Land Between : Intersex Characters in Novels and Memoir

by Rob Ridinger

The subject of persons born with the physical characteristics of both genders has long been one that has fascinated writers, both within and outside the medical profession. Given that most of the reading population in both Europe and North America had little awareness of (or access to) articles in professional medical journals, concepts of the lived experiences of these people were most accessibly expressed in book form, usually as novels but on infrequent occasions as surviving personal accounts. The classical term for them was “hermaphrodite,” a word whose origins lie in Greek mythology, derived from the name of the son of Hermes and Aphrodite, who, when bathing in her fountain, grew together with the nymph Salmacis and thus acquired both male and female characteristics. Much of the slang used in the novels derives from this word in some form, but the term itself is considered offensive by many intersex people who have selected a chosen gender identity.

One of the earliest works of fiction supposedly dealing with intersex people was written in sections between 1886 and 1888 and published in the latter year by A. Piaget in Paris as Sodome. The name on the title page, Henri d’Argis, is a pseudonym used by Alphonse Berty, who also published a volume entitled Gomorrhe in 1889 which centered upon lesbianism. Of particular interest is the preface, which was written by the prominent French poet Paul Verlaine. Michael Finn’s 2012 article on Proust throws some light on what was actually going on: the novel’s author was a member of Verlaines’ circle, and so would have been able to ask him to write a preface for his novel. However, the analysis of the plot reflects more the medical ideas regarding homosexuality prevalent in France at this period than it does portrayal of an intersex character. The only “intersex” theme in Sodome is the attempt by the main character, Jacque Soran, to “cure” himself of being a homosexual by visiting female prostitutes. A possible explanation of this French mindset may be an awareness of the writings of the German homosexual activist Karl Heinrich Ulruchs, whose concept of people we would now call gay or lesbian was to describe them as a “third sex,” with gay men being seen as female souls in male bodies.

One of the earliest works of fiction supposedly dealing with intersex people was written in sections between 1886 and 1888 and published in the latter year by A. Piaget in Paris as Sodome. The name on the title page, Henri d’Argis, is a pseudonym used by Alphonse Berty, who also published a volume entitled Gomorrhe in 1889 which centered upon lesbianism. Of particular interest is the preface, which was written by the prominent French poet Paul Verlaine. Michael Finn’s 2012 article on Proust throws some light on what was actually going on: the novel’s author was a member of Verlaines’ circle, and so would have been able to ask him to write a preface for his novel. However, the analysis of the plot reflects more the medical ideas regarding homosexuality prevalent in France at this period than it does portrayal of an intersex character. The only “intersex” theme in Sodome is the attempt by the main character, Jacque Soran, to “cure” himself of being a homosexual by visiting female prostitutes. A possible explanation of this French mindset may be an awareness of the writings of the German homosexual activist Karl Heinrich Ulruchs, whose concept of people we would now call gay or lesbian was to describe them as a “third sex,” with gay men being seen as female souls in male bodies.

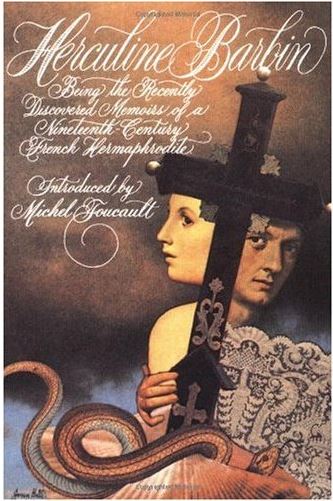

We are on firmer ground with the next fiction work on intersex people which also  appeared in Paris, published sixteen years after Sodome. L’hermaphrodite au couvent is less than two hundred pages and is based on the actual memoirs of a nineteenth century French hermaphrodite, Herculine Barbin, who lived from 1838 to 1868 (Barbin would be the subject of a later biography, but the memoir itself would not be translated and published in English until 1980). Barbin was raised as a female but also had secondary male characteristics such as needing to shave. The manuscript of the memoir was discovered in Barbin’s apartment after he committed suicide in February 1868 by inhaling fumes from his coal gas stove.

appeared in Paris, published sixteen years after Sodome. L’hermaphrodite au couvent is less than two hundred pages and is based on the actual memoirs of a nineteenth century French hermaphrodite, Herculine Barbin, who lived from 1838 to 1868 (Barbin would be the subject of a later biography, but the memoir itself would not be translated and published in English until 1980). Barbin was raised as a female but also had secondary male characteristics such as needing to shave. The manuscript of the memoir was discovered in Barbin’s apartment after he committed suicide in February 1868 by inhaling fumes from his coal gas stove.

The next writer to take up the intersex theme was the noted lesbian author Natalie Barney, whose work, The One Who Is Legion, or, A.D.’s After-Life, appeared in print from Crypt House Press in London in 1930. In this tale of death, resurrection, and spirits, the title character and chief narrator is presented as ungendered. The title is a clear reference to a verse from the fifth chapter of the Gospel of Mark describing the casting out of unclean spirits possessing a man, of whom Jesus asks his name, to which he replies “my name is Legion, for we are many.” The intersex connection here is that the narrator admits to having more than one sexual identity, both male and female, and throughout the book the question of what gender to ascribe to A.D is a constant challenge to the readers’ powers of analysis.

The sexual revolution of the 1960s energized freer discussion of all matters relating to gender, laying the groundwork for the rise of a body of works in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. In 1971, Greenleaf Classics, a paperback house specializing in adult books, published a novel by Linda Dubreiul, titled Morfie, that dealt with the theme of intersex identity (emphasized by some very surreal cover art). A more accessible and lengthy treatment of intersex identity was written in 1972 by Alan Friedman and nominated for the National Book Award in 1973. Hermaphrodeity (parts of which had appeared in New American Review and Partisan Review in 1968 and 1970) presents the autobiography of a fictional poet, M.W. Niemann, who is an hermaphrodite, and his/her life arc through identities as varied as archaeologist, teen punk, fertility goddess, physicist, and Nobel laureate. The title word itself is taken from Ben Jonson’s classic play “The Alchemist”, first performed in 1610, specifically from a dialogue by the title character, Subtle, on the interaction of male and female principles in the transmutation of base metals into gold. The last name of the character can also be read as a word play on the German word niemand, “no one,” indicating that the individual has no clear identity.

The restoration of the story of Herculine Barbin to accessible French literature also began in the 1970s with the publication of Herculine Barbin dite Alexina B. by the Gallimard house in Paris in 1978, with an introduction written by no less a figure than Michel Foucault. Two years later, the French work was translated and published by Pantheon Books of New York as Herculine Barbin: being the recently discovered memoirs of a nineteenth-century French hermaphrodite. The 1980 edition makes available an English text of Foucault’s introduction, which is valuable for its discussion of the way in which the condition of being an hermaphrodite was regarded in France before and during Barbin’s lifetime (and certain medico-legal texts which were influential in shaping the perception of such people). The American edition also includes a translation of an 1893 story by Oscar Panizza, “A Scandal at the Convent” which was based upon Barbin’s case.

The 1990s also witnessed the appearance of an intersex character from a recognized Sikh journalist and author in India, Khushwant Singh. The New Delhi branch of Penguin Books issued Delhi: A Novel as the tale of the journey across six centuries of this city’s complex, colorful, and sometimes brutal history by a journalist, who meets and befriends and falls in love with a hijra, Bhagwati, who then accompanies him. The term hijra in Indian English refers to a person who possesses the characteristics of both male and female and is considered to be neither- the term is amorphous enough to include the Western categories of eunuchs and transvestites as well as hermaphrodites. Its chronological treatment of a specific geographic location will remind American readers of the approach taken by James Michener in such works as Hawaii. The text does, however, assume a familiarity with Indian history and so readers may want to have a reference such as The Cambridge Encyclopedia of India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Nepal, Bhutan, and the Maldives handy. In the preface to Delhi, Khushwant Singh notes that the writing of this work took twenty-five years and that its aim was to share with the reader his love for all the faces of his city. The novel does not seem to have made an impact outside the South Asian market, as reviews of it are few, although Singh notes that its first three printings quickly sold out.

The 1990s also witnessed the appearance of an intersex character from a recognized Sikh journalist and author in India, Khushwant Singh. The New Delhi branch of Penguin Books issued Delhi: A Novel as the tale of the journey across six centuries of this city’s complex, colorful, and sometimes brutal history by a journalist, who meets and befriends and falls in love with a hijra, Bhagwati, who then accompanies him. The term hijra in Indian English refers to a person who possesses the characteristics of both male and female and is considered to be neither- the term is amorphous enough to include the Western categories of eunuchs and transvestites as well as hermaphrodites. Its chronological treatment of a specific geographic location will remind American readers of the approach taken by James Michener in such works as Hawaii. The text does, however, assume a familiarity with Indian history and so readers may want to have a reference such as The Cambridge Encyclopedia of India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Nepal, Bhutan, and the Maldives handy. In the preface to Delhi, Khushwant Singh notes that the writing of this work took twenty-five years and that its aim was to share with the reader his love for all the faces of his city. The novel does not seem to have made an impact outside the South Asian market, as reviews of it are few, although Singh notes that its first three printings quickly sold out.

In 1992, science fiction author Thomas T. Thomas created the title character of  Crygender, a hermaphrodite who has been constructed so that it is impossible to determine an individual gender. Set in a future San Francisco on the island of Alcatraz (which has been purchased by a Japanese company and renamed Babylon), Crygender is the proprietor of a world where anything can be had for the right price- even death.

Crygender, a hermaphrodite who has been constructed so that it is impossible to determine an individual gender. Set in a future San Francisco on the island of Alcatraz (which has been purchased by a Japanese company and renamed Babylon), Crygender is the proprietor of a world where anything can be had for the right price- even death.

Ten years later, a work appeared which may be more familiar to LGBT readers, as it was part of the pool of titles examined for the Stonewall Award. Jeffrey Eugenides’ Middlesex tells the story of Calliope, who in her adolescence recognizes her identity as a hermaphrodite and works to uncover her past. The book was recognized in the 2003 Stonewall Awards as an honor book in literature. Hermaphrodeity was also reprinted in 2002 by Authors Choice Press in San Jose. In 2006, British science fiction writer Mary Gentle published a two-volume series of books with an intersex character as protagonist, set in an alternate universe where Carthage has survived and is now a formidable medieval power. Ilario: A Novel of the First History follows the title character’s life and growth from an abandoned foundling to his eventual rise to a position at court as King’s Freak and his political adventures. And in 2008, the University of Western Australia Press published Amanda Curtin’s novel The Sinkings, where a nineteenth century murder (whose victim was described by various contemporary authorities as both a woman and a man) is investigated one hundred years later.

The second decade of the twenty-first century opened with a novel that continued the trend of placing intersex characters in cultures other than contemporary America, Kathleen Winter’s Annabel. This tale is of a child born intersex but raised as a boy in a small town in Labrador and his search to more truly realize both identities by moving to an urban area. Annabel was recognized by several Canadian literary competitions by being placed on their shortlists in 2010, and in 2014 was chosen for the Canada Reads completion. It was not, however, well received by the world’s intersex community, being challenged for using incorrect stereotypes as plot devices.

This period is also notable for the number of books which appeared featuring characters who are transgender, further complicating the search for fiction treating intersex people. A useful resource for librarians seeking to build their collections in this genre is the list “Hermaphrodite & Intersex Main Characters” (https://www.goodreads.com/list/show/35477.Hermaphrodite_Intersex_Main_Characters ) on the goodreads website, which offers both fiction and nonfiction works. The young adult market has proven to be a venue where intersex characters have appeared with fair regularity in the years since Annabel. Titles here include None of the Above by I.W. Gregorio (2015), the Micah Grey series of three books issued between 2013 and 2014, Abigail Tarttelin’s Golden Boy (2013), Lianne Simon’s Confessions of A Teenage Hermaphrodite (2012),and Double Exposure by Bridget Birdsall (2014). The familiar character of the unmarried female relative, long a part of the literatures of the American South, is given a new twist as intersex by Libby Ware in Lum, a novel set in the North Carolina hills in the 1930s with traditional lifeways being overturned by the construction of the Blue Ridge Parkway. And, coming full circle, the poet Aaron Aaps in 2015 published Dear Herculine, a prizewinning volume of poetry and texts modeled on the memoir by Herculine Barbin which had first demonstrated that intersex people had their own distinct voices and that they would be heard.

References

Barbin, Herculine. Herculine Barbin dite Alexina B. / with a preface by Michel Foucault. [Paris]: Gallimard, 1978.

Barbin, Herculine. Herculine Barbin :being the recently discovered memoirs of a nineteenth-century French hermaphrodite / with a preface by Michel Foucault. (English translation of 1978 French original.) New York: Pantheon Books, 1980.

Barney, Natalie Clifford. The One Who is Legion, or, A.D.’s After-Life. London: Crypt House Press, 1930.

Birdsall, Bridget. Double Exposure. New York: Sky Pony Press, 2014.

The Cambridge Encyclopedia of India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Nepal, Bhutan, and the Maldives. Cambridge University Press, 1989.

Caufeynon, Docteur. L’hermaphrodite au couvent. Paris:, Librairie P. Fort ; L. Chaubard, Successeur, 1904.

Curtin Amanda. The Sinkings. Crawley, W.A.: University of Western Australia Press, 2008.

d’Argis, Henri. Sodome. Paris: A. Piaget, 1888.

d’Argis, Henri. Gomorrhe. Paris: Charles, 1889.

Eugenides, Jeffrey. Middlesex. New York: Picador, 2002.

Friedman, Alan. Hermaphrodeity: The Autobiography of A Poet. New York: Knopf, 1972.

Gregorio, I.W. None of the Above. New York, NY: Balzer + Bray, 2015.

The HarperCollins Book of New Indian Fiction : Contemporary Writing in English, edited by Khushwant Singh. New Delhi; New York, NY: HarperCollins Publishers, 2005.

Michener, James. Hawaii.

“Hermaphrodite.” Oxford English Dictionary. http://www.oed.com/view/Entry/86249?redirectedFrom=hermaphrodite#eid. Accessed 8 September 2015.

“Hermaphrodite and Intersex Main Characters.”

http://www.goodreads.com/list/show/35477.Hermaphrodite_Intersex_Main_Character. Accessed 3 September 2015.

“Hijra.” Oxford English Dictionary.

http://www.oed.com/view/Entry/273016?redirectedFrom=hijra#eid. Accessed 8 September 2015.

Simon, Lianne. Confessions of A Teenage Hermaphrodite. Lawrence, GA: Faie Miss Press, 2012.

Singh, Khushwant. Delhi: A Novel. New Delhi: Penguin, 1990.

Tarttelin, Abigail. Golden Boy. New York: Atria Books, 2013.

Ware, Libby. Lum: A Novel. Berkeley, California: She Writes Press, 2015.

Winter, Kathleen. Annabel. New York: Black Cat , 2010.

______________________________________

Copyright R. Ridinger 2015