Seasons of the pandemic and some books that bore witness (2020 Small Press Roundup, Part I)

by Rebecca Stoddard

Sometime back in the beginning of November, my computer crashed and took with it several important (to me) documents, including both my notes and narrative of this set of micro-reviews. At first, I thought I might attempt to reconstruct what I had already written (and lost) but then, why? When so many of the works I’ve engaged with over the past year are, in one way or another, grappling with memory and history and telling and retelling the overall fragmented way of being “we” have constructed, I decided instead to very blatantly read this as invitation to reckon with my own memory and go back through these last several months experientially via these micro-reviews. While memory often fails, impressions and impact tend to stick to us and most of these works have lived with me for months—with me, on me, under and around me, in every possible way—and as such, have been granted way more head/physical space than I have shared with anyone since the pandemic began.

To talk about this year though, I have to begin back in 1994/95 (?), when I was working cocktail in a drag bar (The Embers) in Portland, Oregon where I had relocated to with all the determination (read: hubris & privilege) that an upbringing in an almost entirely white Philly suburb promised. I had shown up at the club for a week, relentlessly begged a job until they relented and I, newly “out”, began a shift that began at 9pm and ended months/year later at any club (Slaughters, The Eagle, Scandals, etc.) that, at the time, stayed open long after my own had closed. I mention this because gay bars were where I first learned how queers take care of each other but also, where I first really became aware of the impact Ronald Reagan’s presidency had on the shaping of the AIDS epidemic. This awakening was in fact to be the impetus for my return to school and subsequent (if short-lived) career in social services and HIV work. But for now, or rather, then, I was busy learning a whole new way of being— both as myself and in/with/of a community—and this community came to me, or I to it, as with so many others, inextricably linked via colossal failure, to the Reagans.

I still drag this formative experience around with me and indeed have done so into the current pandemic—one equally plagued by leadership’s refusal to acknowledge—and into Maxe Crandall’s performative book of poetry, The Nancy Reagan Collection. And to arrive in The Nancy Reagan Collection is really to show up at the club in whatever state you find yourself— half bedraggled, likely sleep deprived, but nonetheless fully made up and ready for anything. Part performance, part docu-po, this collection activates several different modes of memory: personal, cultural, collective, temporal and spatial as well as archival. But when I mention memory, I mean both constructed and embodied, and here, sobering facts meet high camp as some pages of poems and/or lines of script are also punctuated with very real, very specific names and death dates. Both the footnotes and the citation list at the back are deep with intertextual pointers and archival referents, directing the attention to that defining aspect of queer culture— the performance of hybridity. And hybridity here gives ample acknowledgement of how crucial archives are to living histories and to lives constantly under threat of erasure. Ie: without the archive, where would we be?

If grappling with the history of HIV/AIDS is, among other things, to reckon with myriad systemic relational valences—estrangement and isolation, unnecessary death and loneliness, and ultimately, too many familial and socio-political failures to list— it is also to begin, as this book reminds us, with an unforgivable lack of acknowledgement. Nancy Reagan (the painfully elusive maternal figure) floats through this text as she does my memory, persistently smiling and chimeric and oblivious, a specter emboldened by likewise historical figures who shared the 80s/90s world stage and who, in turns, also achieved almost mythical presences— Michael and Janet Jackson, Rock Hudson, Freddie Mercury, the Dianas (both Ross and Princess), among many others—and they each have lines, cues and places of entry and exit into and out of the story. The result being almost that of a dream: did it happen? What was said? What was she wearing? Did they really? No! Yes?? All the hallmarks of queer theater are here: gossip and drag collide with the hyper-real, the hyper-real meets the surreal, the dream morphs in and out of a nightmare and yes, sadly and dramatically, the nightmare really did happen and now, all that we have to show for it is this t-shirt: We hate Nancy Reagan. Which is to say, that this book is the gayest possible revue, in book form—fun and funny and fantastical and campy and deeply dark/infinitely heartbreaking. If you are anything like me you will read and re-read it, fantasizing about the day we can once again share an audience and applaud for the performance of these pages.

The Nancy Reagan Collection

Maxe Crandall

Futurepoem, 2020, 184 pgs

ISBN: 978-1733038416

But back again to this decade, this pandemic year and this just recently passed through long, lonely summer, when I still felt the possibility of being out in an open space, in a desert, on a prairie, or really any kind of environment that recalls a Nancy Holt project where objects appear, laid bare in undifferentiated landscapes, and where each glance renders a newness or revelation to that of the viewer. I had for a time this summer, the fantasy that this deliberate attention was exactly the kind that I could hunt out and endure while the pandemic loomed all around us. IE: I was itchy for the desert and stillness and enough room to think through something that the last few months made impossible with its constant barrage of drama. But because time was allowed to unfold within its own dimensions and demands and because so much chaos was still all around, growing by the minute it seemed, pulling our attention at every turn, what else was there to do but find myself when I could, in quick breaks, simply on my couch, with Kimberly Alidio’s crystalline, : once teeth bones coral :, attuning to each cluster of words, each seemingly-effortless epiphany. Alidio’s book of seven poems linger on and about and throughout the pages, both spatially and semantically, with very little connective tissue. There is often far more white space than text, far more time for thought, for meaning making, for consideration, and as such the stark words often collide with each other and the space around them forming both echo and location. Lorine Niedecker’s ghost is called upon in the first poem and communities and affinities suggest their way throughout the whole of the book, albeit delicately. The pages are surprising, sexy, deadpan, sometimes banal or blunt, and often sensual evocations, always deconstructed and moving despite their fixed spots. As with waking, how one might make the bed and go about the day somehow all the while recording but also unmaking the day and then unmaking and returning to the bed only to wake and begin again, feeding and wandering, appearing and un-appearing, turning and returning to light and to shadow only to gently lead us out again. This book is hypnotizing in the most minimalistic way— poems that dilate the attention to view each object on its own while simultaneously seeing the entire landscape; as if the objects (words, phrases, clusters, meanings) are both being and environment.

: once teeth bones coral :

Kimberly Alidio

Belladonna, 2020, 144 pgs

ISBN: 978-0-9988439-4-0

Speaking of being and attention and environment, the newest release by Ellen Fullman, on her long-stringed instrument with collaborator/partner, the cellist, Theresa Wong, has been on pretty steady rotation in my house since its release in early fall. It would not be all too far reaching to say that a defining element of these last few months, here in Sonoma County, has been that of ambient light, of ambient smells and the sounds that make up our lived-in environment. From the night-long gusts of wind and fugitive red-orange-yellow glow of light during fire season to the relentless omnipresence of smoke and the eerie, remarkable stillness that followed. During the less dramatic weeks of this fall/winter, Harbors offered a kind of retreat from the otherwise undifferentiated now-ness of our home, on many an undifferentiated morning/afternoon/evening where time simply existed with few distinctions. During the more dramatic weeks, however, Harbors acted as exactly that, as meditative harbor. The album is immersive and almost deliverance-like in its ability to transport, the attunement drawing out an awareness of self, of other, of bodies in place and time filling out this home we seem to be such a living part of: where Wong’s cello might be the lungs, Fullman’s vibratory drone like that of blood. That is, this spare record summons an attunement not just to being home but what it is to be home in this Bay Area Estuary we are a part of: to tides and to water, of the fog coming around the surrounding hills, of saturation, of waves, of harmonics and droning. A good reminder when I needed it— that things go on and fire seasons end just as this pandemic will likewise one day end.

Harbors

Ellen Fullman & Theresa Wong

Room40, 2020

Deep listening is also a cue for how one might best enter The way a line hallucinates its own linearity. Danielle Vogel is a poet, ceramicist, herbalist, ceremonialist who creates work that one might even describe, like the long stringed instrument, as an actual vibration. If you have ever sat Zazen (or maybe any similar meditative practice, Idk), then probably you are familiar with broken promise of linearity. No end, no beginning but sitting. And while sitting: following the line of the breath, dropping the line, picking up the line, breaking the line, closing the line into a circle, breaking out of the circle to be part of the whole and realizing there was never a line to begin with so returning to the “beginning”, which is actually just to say, the breath, or the present and being. And everything else between being and feeling and thinking and letting and breathing and breathing and breathing and sitting. What comes also goes, what gets found, gets added, what gets added eventually decomposes. If I had to describe this book, I might liken it to the skin on the person on the cushion—pulled over the body as it lives and grieves and grows and just keeps being. The body accrues and accretes, the word and time are all pulled into filaments of “The present continuous.” Part poem, part essay, this collection of fragmented, dissociative material pulls together, holds together, the body as it heals.

And I might describe Edges and Fray: On Language, Presence, and (invisible) Animal Architectures, Vogel’s 2019 compilation of nests (language), each lovingly bundled and extended as if offering a summer, or spring, any season that might attend to fragments, to wind and water, to flight and to so many feathers. In this volume, Vogel uses language as animality to situate the reader in a world of micro-movements. This time, the organizing principle isn’t so much the breath but shelters and habitats found in the natural world. In fact, I began this book in the late summer, on the banks of a very still river and it seems not accidental that both books came to me this year when to read them together is to settle into a state of wonder, to find both the inside and outside, that is, a kind of completion that comes from living through something, possibly unendurable, and trusting the self and then so too, trusting the world in the most micro of senses, mirrored both in and outside, as above so below. Rocks, wings, flight, field, body, thoughts, memory, words. Husks and mud cups, “to start where one lands/to hardly alter the surface of the earth”. It is, in fact, difficult for me not to read these two books together: one as filament, string, grass, the other woven, as nest. Both as prayer and alms.

The Way a Line Hallucinates its own Linearity

Danielle Vogel

Red Hen Press, 2020, 80pp

ISBN: 9781597098212

Edges and Fray

Danielle Vogel

Wesley Univ Press, 2019, 112pp

ISBN: 9780819579225

And to talk about weaving is to talk about fragments is to talk about collage. All of which seem to be how time and our lives are working right now and why it seems both a world away and also yesterday when I was back in April reading Julia Bloch as the pandemic began. Hardly able to bear the situation I found myself in both personally and in our collective experience—a country both denying but deeply experiencing simultaneously a pandemic and the collapse of social systems as their unsustainability became apparent. The Sacramento of Desire arrived just as I was yearning for (and mentally planning) a road trip through California as reprieve from shelter in place orders that had already far outlasted what we were expecting (ha!). At the time, my mind was fresh with a winter trip I had taken to Sacramento: a ride through the valley, a room on a river boat, ice skating and cars and railroads and industry and yes, settlerism. These thoughts stayed with me through Bloch’s book where objects appear only to disappear, threads are criss-crossed and comingled, where the body is both harbinger and question, and where community, as documented in substantial ekphrastic notes to the text, is one that is deep and thick and what carries us when longings—in this case the longing for conception— ultimately, betray us. The head spinning healthcare process does not stand up to scrutiny and its roots in the making of a state are suggested in the “Sacramento” of these pages. I was reminded of so many documents I had seen on my recent trip to Sacramento—journals and letters from those early “settlers” who, unknowingly, left an undeniable account of colonizing. Bloch’s poems are text blocks that read like fragments from a journal where thoughts, observations, accounts and recollections collide. As with Bloch’s previous two books of poetry, these poems have that unmistakable feel of a road trip: colors and objects passing by with definitive place-ness, specificities both noted and recorded as something more general, more suggested. The poems were written through the IVF process and both the physical and gathered body endure where the process doesn’t and ultimately offer a weave so tight they bear testimony to the power of community.

The Sacramento of Desire

Julia Bloch

Sidebrow Books, 2020, 93 pgs

ISBN: 9781940090122

California indeed seems to be the material from which much of what I have clung to this never-ending year was made. Joon Oluchi Lee’s Neotenica came floating into my spring along with an aggressive dissolution of my attention and the occasional total inability to read or focus or think. So, it turned out that this book travelled with me for a while before I actually dropped fully down into its brief but deeply satisfying pages. There is something so naked in this short novel, full of both honesty and absurdity, the characters are almost unbelievably themselves, as if they couldn’t possibly be anything else, and at the heart of everything is a radical femininity. The San Francisco in Neotenica reads as both familiar and entirely unknown and descriptions of the banal or by-the-way also read as brilliance, cold as hot, and sexy as infinitely chilling, etc. Time jumps, characters continually reveal themselves, in equal measure as both mundane and otherworldly and these vignettes move through seemingly random days as one does—doing the laundry, walking with a child, having an orgasm— as if a kind of weightlessness exists in all things. Which is to say that fluidity happens in all things on these small pages, there is a newness around every bend and in the end, I found myself desiring the characters in so many ways—desiring to know them, to be them, to write them, and to leave them, etc. There is a slipperiness in the materiality here and it is alluring. I might even say Oluchi Lee’s Bay Area of the not-so-distant past reads a lot like Young Ae’s husband, a completely confident, “dainty penis” top, who is at once uninterested but also available for any possibility. And these days, what more could we want?

Neotenica

Joon Oluchi Lee

Nightboat Books, 2020, 106 pgs

ISBN: 9781643620206

But if the film of this high summer rendered negotiations and bouts of alternative possible lives and ambitions it was only as they erupted from the infinite “no” of late spring. While protesting the murders of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor, Sean Monterrosa was shot and killed by Vallejo PD just minutes from where I was, at the time, sheltering in place, and there, on my bedside table, to the soundtrack of sirens and helicopters was Cyrée Jarelle Johnson’s Slingshot, holding up a mirror to the moment, foretelling the racial reckoning 500 years in the making, through its own poetic questioning of liberation. Which is to say, the poems in this book have already lived out systemic ineptitude and are themselves the embodiment of both radical refusal and self-acceptance. In other words, Jarelle Johnson refuses to do what you think they’re going to do with lyric, narrative, or even the body. These poems don’t care if you have time or make space for them, they make their own. Language and logic here are configured, disfigured, refigured only to find you and begin again, insisting you witness. These are completely unapologetic poems shot-thru with fierce evidence of a life being negotiated in relation to the self, to the state, and to the john with self-actualized determination, taking life on their own terms, constantly asking what would you do if you were pushed? There is intimacy and lyric but no room for fragility here, no long romantic, pastoral musings and no, you may not cling to outmoded formalisms without facing a mirror, full frontal. As the title suggests, these poems are projectiles, and the shape of them, handmade. And what do these poems wish for? “If you must be raped, may all your rapes/ be short rapes…May every fragment locate its escape route…May you glide along the blade of truth: nothing/could take as long, or as much, as this took.”

Slingshot

Cyrée Jarelle Johnson

Nightboat Books, 2019, 80 pgs

ISBN: 9781643620091

Just as the pandemic snaking through us seemed to level off, if only a little, fall came along to hit us like a brick wall, reminding us once again of the reciprocal ways we define and are defined by our environment. The now annual fires were back in Sonoma County and they were bigger and more apocalyptic than ever. Smoke inflated our already dry lungs, and alerts lit up our phones every couple hours announcing closures and evacs and warning after warning upgraded to emergency upgraded to literally, “Get out now.” And right there in my hand and in my head lingered Laura Elrick’s seemingly prophetic What This Breathing, asking the very thing I had been asking myself, that hopefully many of us are asking of ourselves—what does it mean to live now, deeply inside of climate catastrophe? What does it mean to live inside lines like, “because you want/yes want to live and/that is the start of complicity…an anxiety in the host you know you are/and will learn you want to no, must kill.” These poems are populated with species and industry, environment and technology, family and love in both its historical formations, “I drag my women behind me to pass through the grove of she’s she has become” and its future tenses, always asking what we are going to do about what we have already done, about our roles and responsibilities to this habitat and also, rightly, to the future, “what kind of art should be made for it? If there will have been a human story/but not the one we tell ourselves.” I cannot stress enough how prominently this book figured into a time when I was literally finding it hard to breath in a burning county where we are all, annually, fleeing and returning, some of us to nothing, and how important it feels to be asking the very questions being asked in this collection.

What This Breathing

Laura Elrick

The Elephants, 2020, 96 pgs

ISBN: 978-1988979380

But while these seasons have been difficult, one of the boons to life at home is, without a doubt, the emergence of a robust online programming that makes possible access to a virtual cultural life in ways previously unrealized. The Remote Intimacies series commissioned and curated by ONE Archives and the Leslie-Lohman museum is one not to miss. The first program, Graduation by Brontez Purnell, described on the website as “a live action bedroom performance” , began with a live feed in Purnell’s apartment, specifically bedroom and bathroom, and in Purnell’s usual fashion, offered a pretty candid view of the artist in states of undress—at times covered with flowers, at times lathering their UC Berkeley sweatshirt in a shower stall (the domestic cleansing the academic?)—bringing attention to the body and the home as sites of performance rather than business as usual on the public stage. This renegotiation of the usual parameters of performance and accessibility, bring attention to the degrees by which our social/personal/financial lives have changed this year and to how much we are mostly now, albeit to differing degrees, all existing within a gig economy. The private here is performance and so conjures that old familiar, feminist mantra that both promises and threatens to illustrate how politically relevant even our most private moments. Given that this year has highlighted all the cracks, flaws and impossible imbalances in our lives, this performance of Black/queer/artist precarity implicates the conditions which many find themselves hustling to string together performances of self to sustain an architecture just barely capable of standing, let alone holding.

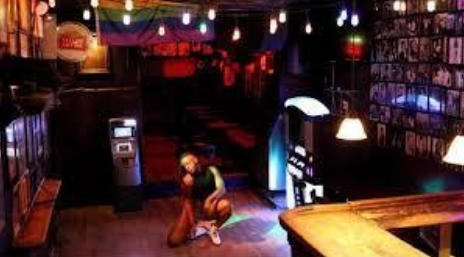

The second in the series was Joseph Liatela’s Vital Response, a videowork where dancers appear, almost ghostlike, in an empty bar, singly, and as if performing for no one. The work is an homage to the important cultural space of the queer bar in its historic dimension as well as future potential for queer social world building and as sites of resistance, protest and communion. From Stonewall to Pulse and everything in between and outside of those two landmark sites of public impact, the queer bar is appealed to here as representative of, if not center of, the social life of queer communities. Vital Response, is also a reminder that, when this pandemic eventually eases and bodies begin to congregate again, the queer bar will be right there, not to recreate, but as Liatela suggests, to restage the future. This program did indeed deliver its reminder during an otherwise lonely-as-hell fall. It is a good reminder that what can come has possibility, that the future can actually be embodied. Sadly, I was not able to attend the third and final fall program featuring Mikki Yamashiro, aka Candy Pain, but I look forward to catching up with the series in the spring.

Image from ONE Archives website: Brontez Purnell, 100 Boyfriends Mixtape/ Episode 3: HOW I SPENT MY SUMMER VACATION, 2020, still from digital video. Courtesy of the artist.

Image from ONE Archives website: VITAL RESPONSE (2020) by Joseph Liatela, dancer: DaJuan Harris

Lots can be said about all this year has taught us, not the least of which is to question nostalgia. Facts get constructed, memory fails/omits/alters/anesthetizes, and retrospect often brings with it an air of superiority and/or sophistication that renders the referent infantilized, simple or otherwise, “innocent.” But in some cases, such as Stephen Grebinski’s Room Service Plus, nostalgia can also be completely alluring, especially when it is deconstructed and/or rearranged to such an extent that that thing one is looking back upon becomes something new, in its own right. This 72 page book is a series of lo-fi collage work derived from VHS tapes found in a fire-damaged bath house. Porn, travel docs, cowboy movies, etc, are collected, combined, and otherwise altered to make up a series of images that locate and relocate the viewers gaze, alongside questions of subjectivity and authorship, panning between deeply layered bodies, landscapes and domestic scenes. The bodies themselves, sometimes de-nuded and anonymous, suggest levels of intimacy while never actually realizing their original pornography. The effect is that of a dream state where the viewer moves with the images as if between the rooms of a dream never fully grasping more than slippery suggestions or solicitations that dissipate just as quickly as they come on. At times those dream rooms take on the quality of a road trip, a shimmery and promiscuous one at that, where the camera, the viewer and the viewed are all constantly in motion, barely taking note of flickering trees, mountains, buildings, bodies as they pass us by.

Image:

Room Service Plus

Stephen Grebinski

Edition of 125

5×8 inch offset printed

72 pages

As this year too seems to have passed by, surprising in every conceivable way—as a slippery, difficult, elusive thing that will no doubt lodge itself inside memory with all of the bulk and the heat and the purely acrid taste it has created. In fact, it seems near impossible to consider what life was like a year ago: one’s intentions or negotiations which may now seem silly, unattainable or even just forgotten. I do however recall having hopes last winter of writing a quarterly review, and finding myself with a stack, at the top of which was a little book that would take me forward in time to this review, and that is to say, back in time to the epidemic that foretold the current one, to the man who stood accused of starting it all. I fill this room with the echo of many voices is a stunning chapbook by Eric Sneathen filled with charming, warm, sometimes heartbreaking, and more often than not, sexy-as-all-get-out sonnets, collaged from ephemera from the life of Gaëtan Dugas, or, as he had been incorrectly but persistently deemed, “patient zero.” The chapbook book reads as a kind of collective memory—an ode to gay bar life, to the thrill of the crush and the undeniability of the body. HIV/AIDS is here but more real than the disease are the actual human bodies, woven together out of fragments but somehow fantastically embodied, desirous and deeply invested in communal joy where any lyric notion appears accidental but also a matter of course. As these long seasons have suggested, if there is indeed anything I feel nostalgic for it is not for “life before,” but it might be for something recorded in this tiny book— something strangely organic and humanly necessary, inevitable even, some un-nameable thing that is only ever a matter of locating: “a wilderness of hearts/And fears. What else can I say? A record/Of real beauty lives in the house on fire.”

I fill this room with the echo of many voices

Eric Sneathen

Eyelet Press, 2019, 40 pgs

For inquires, comments, suggestions, and/or with book review requests, please contact me at Rstoddard@santarosa.edu