Off The Shelf #23 Around the Samovar : Tracking LGBT Russian Histories

by Rob Ridinger

Dedicated to the memory of Mikhail Kuzmin, Peter Tchaikovsky and Igor Kon

The topic of homosexuality and its histories within the lands that make up today’s Russian Federation has been, until recently, familiar chiefly to students of Eastern European or Slavic studies, particularly in the fields of literature, art and music. While the censorship mechanisms in place during Tsarist times and the views on homosexuality held by the Russian Orthodox clergy severely limited discussion or expression of same-sex loves, such relationships did occur. This essay will explore the range of works available in English on LGBT people (both historic and contemporary) whose lives were interwoven with the society and cultures of Russia. Researchers should be aware that many of the works referred to have not been translated from Russian as yet.

The topic of homosexuality and its histories within the lands that make up today’s Russian Federation has been, until recently, familiar chiefly to students of Eastern European or Slavic studies, particularly in the fields of literature, art and music. While the censorship mechanisms in place during Tsarist times and the views on homosexuality held by the Russian Orthodox clergy severely limited discussion or expression of same-sex loves, such relationships did occur. This essay will explore the range of works available in English on LGBT people (both historic and contemporary) whose lives were interwoven with the society and cultures of Russia. Researchers should be aware that many of the works referred to have not been translated from Russian as yet.

Any examination of the lives and situations of women and men who were attracted to their own gender in the lands of imperial Russia must take into account the two institutions which provided a substantial part of the social framework: the dominant religious force of the Russian Orthodox Church and the autocratic government of the tsars (and the laws dealing with sexuality which it promulgated and enforced). Russia’ s Orthodox faith had its beginnings in the work of two missionaries from Byzantium, Cyril and Methodius, who were later canonized and who developed the Cyrillic writing system used by Russian and other Slavic languages. From the earliest days of the conversion of Prince Vladimir of Kiev in 988 across the reigns of successive dynasties, the Orthodox Church provided both regular religious instruction and a moral framework for the definition and management of moral and social questions to all classes of Russian society. In contrast to the emphatic condemnation of homosexuality regularly advanced by the Western church under Catholicism, the Orthodox Church functioned in an environment where the definition of masculinity included same-sex relations in the spectrum of possible sexual relations. Punishment for same-sex activities imposed by the Orthodox clergy usually took the form of enacting penances equivalent to those meted out to cases of heterosexual adultery.

The autocracy of Russia’s civil government up to the middle of the nineteenth century ruled a land where the changes introduced to Western European nations by the Industrial Revolution and its attendant processes of urbanization had not occurred. Most of the population outside the cities were peasants bound to the land as serfs, who would not be freed until the Emancipation Act of 1861. Yet even in such a seemingly unchanging society, changes in the laws affecting same-sex relationships between men had begun, with the first notable legal limitation taking place in the early eighteenth century under Peter the Great as part of his massive reshaping of Russian society by introducing political changes influenced by Western European trends. In 1716, he banned sodomy for sailors and soldiers as part of his modernization program, but it was not until 1835 that Tsar Nicholas I extended this legal regulation to the civilian population, with the aim of promoting civic and religious values. The transformations undergone by Russian society during the nineteenth century both foreshadowed the October Revolution of 1917 and provided the background to some of the most famous creative works by artists oriented toward their own gender, chiefly in the fields of music and literature. Perhaps the most familiar example of this group is the composer Peter Tschaikovsky.

The term “Silver Age“ is used in Russian literary history for the period of time beginning in the 1890s and including the dozen years between the Revolution of 1905 and the February 1917 revolution which instituted a parliamentary system . The years between 1905 and 1917 were especially marked by an  array of poets and writers who dealt with homosexuality in their works. Perhaps the most famous example is Mikhail Kuzmin (1872-1936), whose 1906 novel Wings was the first “gay novel” ever published in Russia. This was also an era which saw an explosion of diverse artistic and literary schools, among whose members were several openly lesbian and gay authors of both prose and poetry. Prominent poets in this group included Nikolai Kliuev (1884-1937), Marina Tsvetaeva (1892-1941), Anna Akhmatova (1889-1966) and Sofia Parnok (1885-1933), who was described as the “Russian Sappho” – thus, for a brief period, being lesbian or gay was no longer an identity that had to be hidden, but one which could be theoretically openly celebrated.

array of poets and writers who dealt with homosexuality in their works. Perhaps the most famous example is Mikhail Kuzmin (1872-1936), whose 1906 novel Wings was the first “gay novel” ever published in Russia. This was also an era which saw an explosion of diverse artistic and literary schools, among whose members were several openly lesbian and gay authors of both prose and poetry. Prominent poets in this group included Nikolai Kliuev (1884-1937), Marina Tsvetaeva (1892-1941), Anna Akhmatova (1889-1966) and Sofia Parnok (1885-1933), who was described as the “Russian Sappho” – thus, for a brief period, being lesbian or gay was no longer an identity that had to be hidden, but one which could be theoretically openly celebrated.

In 1933, male homosexuality was recriminalized with the addition of Article 121 to the law code, which would remain in force until 1993. The penalty if convicted was five years hard labor, but no legal notice was taken of lesbianism. The new repressive environment brought the experimentation of writers and artists to a firm halt, at least in public, and many of them perished in the purges which characterized the Stalinist regime. The invasion of the Soviet Union by Nazi Germany and the subsequent, widespread destruction further reinforced the disruption of life for lesbian and gay citizens of Russia. The postwar years of rebuilding continued to be ones of repression for the LGBT population, who did not see themselves reflected in the myths created by the government to inspire and sustain the new socialist world of Soviet society which emphasized the ethic of working for the people and supported heterosexuality as the norm. Historians were trained to regard any interest in sexuality as an element of biography or literary analysis as more suitable for the medical profession than their own craft, and primary sources on such figures as Mikhail Kuzmin that might have challenged the accepted model of sexuality were carefully sequestered.

It was not until the 1970s that the first historical interpretations of LGBT life in Russia presenting a more diverse picture of what had existed began to appear from the work of Simon Karlinsky. Between 1976 and 1982, three articles on “Russia’s Gay Literature and History”, ” Death and Resurrection of Mikhail  Kuzmin “ and “ Gay Life Before the Soviets: Revisionism Revised “ were published in Gay Sunshine, Slavic Review and THE ADVOCATE respectively . The Gay Sunshine article was later included in the 1993 anthology Gay Roots : Twenty Years of Gay Sunshine : An Anthology of Gay History, Sex, Politics, and Culture edited by Winston Leyland with substantial additional materials added under the title “ Russia’s Gay History and Literature from the Eleventh to the Twentieth Centuries.” Karlinsky also contributed a chapter on “Russia’s Gay Literature and Culture: the Impact of the October Revolution” to the 1990 anthology Hidden From History: Reclaiming the Gay and Lesbian Past edited by Martin Duberman, Martha Vicinus and George Chauncey. Both of these essays provide the reader with a detailed picture of the complex social world shaped by the lesbian and gay writers and artists of Russia prior to the October 1917 revolution and the somber fates many of them met in the new Soviet world.

Kuzmin “ and “ Gay Life Before the Soviets: Revisionism Revised “ were published in Gay Sunshine, Slavic Review and THE ADVOCATE respectively . The Gay Sunshine article was later included in the 1993 anthology Gay Roots : Twenty Years of Gay Sunshine : An Anthology of Gay History, Sex, Politics, and Culture edited by Winston Leyland with substantial additional materials added under the title “ Russia’s Gay History and Literature from the Eleventh to the Twentieth Centuries.” Karlinsky also contributed a chapter on “Russia’s Gay Literature and Culture: the Impact of the October Revolution” to the 1990 anthology Hidden From History: Reclaiming the Gay and Lesbian Past edited by Martin Duberman, Martha Vicinus and George Chauncey. Both of these essays provide the reader with a detailed picture of the complex social world shaped by the lesbian and gay writers and artists of Russia prior to the October 1917 revolution and the somber fates many of them met in the new Soviet world.

The 1990s continued to be a period of expanded writing activity in English on the Russian community. In  1992, Diana Lewis Burgin penned an article for Slavic Review on “Sophia Parnok and the Writing of a Lesbian Poet’s Life,“ foreshadowing her own full-length biography of the poet which would appear two years later. And in 1993, Daniel Healey’s lengthy article “The Russian Revolution and the Decriminalisation of Homosexuality” was published in the journal Revolutionary Russia. The removal of legal penalties for homosexuality by the Bolsheviks in 1917 as part of the elimination of the Imperial Criminal Code should, in his view, be seen as a political event occurring in a complex environment of influences as diverse as the ways in which the Russian medical community defined and managed homosexuality as a phenomenon and the history of previous attempts to legally address same-sex behavior. He notes that “the medicalization of homosexual acts was an international phenomenon, part of the process by which scientists supplanted clerics in Western nations as the interpreters of sexual normality. Russian scientists imported a range of new sexual categories, including eventually the characterization ‘homosexual’…to describe same-sex erotic behavior.” (Healey 1993: 28-29). This was the period when in Western Europe there was great interest in placing homosexuality within a medical framework, principally in Germany through the efforts of Dr. Magnus Hirschfeld and his associates. The idea of recasting social attitudes towards men and women attracted to their own gender which formed a central part of the work of the German lesbian and gay movement in the first decades of the twentieth century had no visible counterpart in Russian society, due in part to the majority of the population living outside urban centers where agitation for such change could be visible and effective. Same-sex relations were re-criminalized in the period 1933- 1934, with homosexuality being variously seen as a crime of political subversion and an attribute of fascism (in the opinion of no less prominent a figure than Maksim Gorky.) Healey also notes the relative absence of private businesses serving a homosexual clientele, which could have financed the development of such aspects of a community as publications.

1992, Diana Lewis Burgin penned an article for Slavic Review on “Sophia Parnok and the Writing of a Lesbian Poet’s Life,“ foreshadowing her own full-length biography of the poet which would appear two years later. And in 1993, Daniel Healey’s lengthy article “The Russian Revolution and the Decriminalisation of Homosexuality” was published in the journal Revolutionary Russia. The removal of legal penalties for homosexuality by the Bolsheviks in 1917 as part of the elimination of the Imperial Criminal Code should, in his view, be seen as a political event occurring in a complex environment of influences as diverse as the ways in which the Russian medical community defined and managed homosexuality as a phenomenon and the history of previous attempts to legally address same-sex behavior. He notes that “the medicalization of homosexual acts was an international phenomenon, part of the process by which scientists supplanted clerics in Western nations as the interpreters of sexual normality. Russian scientists imported a range of new sexual categories, including eventually the characterization ‘homosexual’…to describe same-sex erotic behavior.” (Healey 1993: 28-29). This was the period when in Western Europe there was great interest in placing homosexuality within a medical framework, principally in Germany through the efforts of Dr. Magnus Hirschfeld and his associates. The idea of recasting social attitudes towards men and women attracted to their own gender which formed a central part of the work of the German lesbian and gay movement in the first decades of the twentieth century had no visible counterpart in Russian society, due in part to the majority of the population living outside urban centers where agitation for such change could be visible and effective. Same-sex relations were re-criminalized in the period 1933- 1934, with homosexuality being variously seen as a crime of political subversion and an attribute of fascism (in the opinion of no less prominent a figure than Maksim Gorky.) Healey also notes the relative absence of private businesses serving a homosexual clientele, which could have financed the development of such aspects of a community as publications.

In 1994, a sixty-page report written by Masha Gessen was published in San Francisco by the International Gay and Lesbian Human Rights Commission. Titled The Rights of Lesbians and Gay Men in the Russian Federation, it is printed in both English and Russian. The contents offer a detailed view of the legal situation of gays and lesbians in Russia during the Gorbachev era, and describe the uses of law in the historic repression of this part of the population, based on case information gathered by many activists both within and outside Russia. Topics addressed include the elimination of the right to privacy in Soviet law, how the anti-sodomy law was enforced, the application of forced psychiatric treatment to lesbians (including regimens of drugs), and the political realities of the repeal of Article 121.1 (the law prohibiting consensual sex between men). Of particular interest is the section “After the Repeal “, which looks at the actual situation for lesbians and gays in the areas of freedom of expression, freedom of association and assembly, freedom from cruel and unusual punishments (such as imprisonment and forced psychiatric care), the right to privacy, and the limited options for former prisoners to gain legal rehabilitation and damages. The beginnings of the then-contemporary gay rights movement in Russia are placed at a 1990 news conference where the foundation of the newspaper Tema and the formation of the Moscow Union of Sexual Minorities was announced. The report concludes with a set of recommendations for the lesbian and gay community as it tried its wings in the new social and political atmosphere. That environment also witnessed the foundation of Russia’s first publisher for gay books, an enterprise profiled by its director Alexander Shatalov in the 1994 article for Glas : New Russian Writing, “ GLAGOL: Russia’s First Gay Publishing House Flourishing .” The pool of writings on Russian LGBT authors was also augmented in 1994 with the appearance of Diana Burgin Lewis’ lengthy detailed biography Sophia Parnok: The Life and Work of Russia’s Sappho.

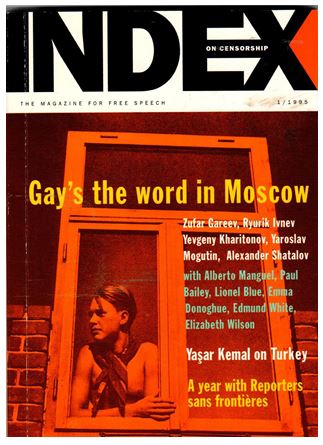

1995 was marked by the publication of a varied group of writings on LGBT Russia from the perspectives of journalism and history. The first of them was the January 1995 issue of Index On Censorship: The Magazine for Free Speech which took as its theme “Gay’s The Word in Moscow.” The principal content of the journal is a mixture of nonfiction articles discussing the history of notable gay and lesbian writers in Russia and translations of stories by contemporary writers and a second interview with Alexander Shatalov on the Glagol publishing company and its projects. Masha Gessen’s lengthy article “Sex in the Media and the Birth of the Sex Media in Russia “ traces in detail the evolution of official government policies on permissible depictions of sexuality beginning in the 1930s up to then-contemporary times, with emphasis placed on the explosion of newspaper and magazine articles frankly dealing with sexuality published during the era of glasnost. Among the LGBT topics discussed is the appearance of Tema, the first gay and lesbian newspaper, founded by Roman Kalinin, and background on historian and sociologist Igor Kon, whose book The Sexual Revolution in Russia: from the Age of the Czars to Today would be published in 1995 by the Free Press as an English translation. Of particular interest is Gessen’s coverage of the first periodical articles to be written on homosexuality and their placement within the realities facing Russian lesbians in the 1980s.

1995 was marked by the publication of a varied group of writings on LGBT Russia from the perspectives of journalism and history. The first of them was the January 1995 issue of Index On Censorship: The Magazine for Free Speech which took as its theme “Gay’s The Word in Moscow.” The principal content of the journal is a mixture of nonfiction articles discussing the history of notable gay and lesbian writers in Russia and translations of stories by contemporary writers and a second interview with Alexander Shatalov on the Glagol publishing company and its projects. Masha Gessen’s lengthy article “Sex in the Media and the Birth of the Sex Media in Russia “ traces in detail the evolution of official government policies on permissible depictions of sexuality beginning in the 1930s up to then-contemporary times, with emphasis placed on the explosion of newspaper and magazine articles frankly dealing with sexuality published during the era of glasnost. Among the LGBT topics discussed is the appearance of Tema, the first gay and lesbian newspaper, founded by Roman Kalinin, and background on historian and sociologist Igor Kon, whose book The Sexual Revolution in Russia: from the Age of the Czars to Today would be published in 1995 by the Free Press as an English translation. Of particular interest is Gessen’s coverage of the first periodical articles to be written on homosexuality and their placement within the realities facing Russian lesbians in the 1980s.

The complexity of Russian attitudes towards matters sexual over several centuries is the subject of the  1995 volume The Sexual Revolution in Russia: from the Age of the Czars to Today by Igor Kon, a sociologist whose writings were at the time of publication “the only nonmedical books on sexuality available in Russia (Kon 1995: 6.) Kon describes the attitudes toward and legal limitations on homosexual behavior in the society of prerevolutionary Russia then includes it as an issue of sexuality during the successive political revolutions enacted to create the Soviet Union, Most of the detailed discussion on the situation of gays and lesbians after 1933 is found in the seventh chapter “Coming Out Into Chaos “whose coverage extends up to 1993. 1995 also saw the publication of an article on “Soviet Policy Toward Male Homosexuality: Its Origins and Historical Root “by historian Laura Engelstein in the Journal of Homosexuality. Her focus is on the period between the Revolution of 1917 and the beginning of the Stalinist era in the 1930s, beginning with the notation of the legal prohibition of sodomy under the imperial law code, whose enforcement was completely prohibited by the end of 1918. A key point of Engelstein’s essay is the detailed exploration of how Russian attitudes and ideologies towards homosexuality (both social and legal) had developed up to the time of the Revolution and their evolution within the new socialist system after the publication of the new criminal code in 1922 until the re-criminalization of sodomy in 1933. She notes that the political dimension of these actions remains to be investigated.

1995 volume The Sexual Revolution in Russia: from the Age of the Czars to Today by Igor Kon, a sociologist whose writings were at the time of publication “the only nonmedical books on sexuality available in Russia (Kon 1995: 6.) Kon describes the attitudes toward and legal limitations on homosexual behavior in the society of prerevolutionary Russia then includes it as an issue of sexuality during the successive political revolutions enacted to create the Soviet Union, Most of the detailed discussion on the situation of gays and lesbians after 1933 is found in the seventh chapter “Coming Out Into Chaos “whose coverage extends up to 1993. 1995 also saw the publication of an article on “Soviet Policy Toward Male Homosexuality: Its Origins and Historical Root “by historian Laura Engelstein in the Journal of Homosexuality. Her focus is on the period between the Revolution of 1917 and the beginning of the Stalinist era in the 1930s, beginning with the notation of the legal prohibition of sodomy under the imperial law code, whose enforcement was completely prohibited by the end of 1918. A key point of Engelstein’s essay is the detailed exploration of how Russian attitudes and ideologies towards homosexuality (both social and legal) had developed up to the time of the Revolution and their evolution within the new socialist system after the publication of the new criminal code in 1922 until the re-criminalization of sodomy in 1933. She notes that the political dimension of these actions remains to be investigated.

The next work to appear dealing with the LGBT population of Russia took a more informal but no less nuanced tone. Journalist David Tuller’s Cracks in the Iron Closet: Travels to Gay & Lesbian Russia is based upon several visits to and periods of residence in post-Gorbachev Russia he made to Russia between 1991 and 1996. The women and men who welcomed Tuller into their networks of friendship and contacts speak from his pages with warmth and endurance and provide a frank view of LGBT reality inside Russian society from the inside. 1996 is also notable for Out Of The Blue:

The next work to appear dealing with the LGBT population of Russia took a more informal but no less nuanced tone. Journalist David Tuller’s Cracks in the Iron Closet: Travels to Gay & Lesbian Russia is based upon several visits to and periods of residence in post-Gorbachev Russia he made to Russia between 1991 and 1996. The women and men who welcomed Tuller into their networks of friendship and contacts speak from his pages with warmth and endurance and provide a frank view of LGBT reality inside Russian society from the inside. 1996 is also notable for Out Of The Blue:  Russia’s Hidden Gay Literature: An Anthology published by Gay Sunshine Press in San Francisco. The collection opens with an introduction by Simon Karlinsky on Russian gay literature and history, then moves chronologically from the nineteenth century to the 1990s, presenting English translations of excerpts from published and unpublished novels, plays and diaries, letters, essays, and poems. Writers included range from Alexander Pushkin and Leo Tolstoy through the Silver Age authors such as Mikhail Kuzmin and Nikolai Kliuev to works produced either in exile or circulated privately as samizdat and then-current literature from writers active in the later twentieth century. The focus on the retrieval of Russia’s tradition of LGBT writing continued in 1998 in with The Columbia Anthology of Gay Literature : Readings from Western Antiquity to the Present Day, which featured a section on “ Erotic Revolutionaries : Russian Literature ( 1836-1922 ) with selections from the writings of Alexander Pushkin, Nikolai Klyuev, Sergei Esenin and Mikhail Kuzmin. 1998 also saw the acceptance of a doctoral thesis at the University of Toronto written by Daniel Healey, Homosexual Desire in Revolutionary Russia:

Russia’s Hidden Gay Literature: An Anthology published by Gay Sunshine Press in San Francisco. The collection opens with an introduction by Simon Karlinsky on Russian gay literature and history, then moves chronologically from the nineteenth century to the 1990s, presenting English translations of excerpts from published and unpublished novels, plays and diaries, letters, essays, and poems. Writers included range from Alexander Pushkin and Leo Tolstoy through the Silver Age authors such as Mikhail Kuzmin and Nikolai Kliuev to works produced either in exile or circulated privately as samizdat and then-current literature from writers active in the later twentieth century. The focus on the retrieval of Russia’s tradition of LGBT writing continued in 1998 in with The Columbia Anthology of Gay Literature : Readings from Western Antiquity to the Present Day, which featured a section on “ Erotic Revolutionaries : Russian Literature ( 1836-1922 ) with selections from the writings of Alexander Pushkin, Nikolai Klyuev, Sergei Esenin and Mikhail Kuzmin. 1998 also saw the acceptance of a doctoral thesis at the University of Toronto written by Daniel Healey, Homosexual Desire in Revolutionary Russia:  Public and Hidden Transcripts, 1917-1941, later issued as Homosexual Desire in Revolutionary Russia : the Regulation of Sexual and Gender Dissent by the University of Chicago Press in 2001. The “transcripts” of the title are primary medical, administrative and legal records produced from the early years of the Soviet government up to the entry of Russia into World War II. Healey’s work was complemented in 1999 by Laurie Essig’s thoughtful study Queer in Russia: A Story of Sex, Self, and the Other, based upon research done primarily in 1994 and centered on “that moment when objects of expert knowledge and public hostility became subjects of their own desires “(Essig: xi), the emergence of some lesbians and gay men from invisibility to kindle a public dialogue on homosexuals for the first time since the Silver Age (1905-1917). One of the major figures of that era was also re-introduced to the literary public of the world with John Malmstad and Nikolay Bogomolov’s 1999 biography Mikhail Kuzmin: A Life in Art from Harvard University Press. One of his plays, “The Dangerous Precaution, “also appeared that year in the theatre anthology Lovesick : Modernist Plays of Same-sex Love, 1894-1925, published by Routledge.

Public and Hidden Transcripts, 1917-1941, later issued as Homosexual Desire in Revolutionary Russia : the Regulation of Sexual and Gender Dissent by the University of Chicago Press in 2001. The “transcripts” of the title are primary medical, administrative and legal records produced from the early years of the Soviet government up to the entry of Russia into World War II. Healey’s work was complemented in 1999 by Laurie Essig’s thoughtful study Queer in Russia: A Story of Sex, Self, and the Other, based upon research done primarily in 1994 and centered on “that moment when objects of expert knowledge and public hostility became subjects of their own desires “(Essig: xi), the emergence of some lesbians and gay men from invisibility to kindle a public dialogue on homosexuals for the first time since the Silver Age (1905-1917). One of the major figures of that era was also re-introduced to the literary public of the world with John Malmstad and Nikolay Bogomolov’s 1999 biography Mikhail Kuzmin: A Life in Art from Harvard University Press. One of his plays, “The Dangerous Precaution, “also appeared that year in the theatre anthology Lovesick : Modernist Plays of Same-sex Love, 1894-1925, published by Routledge.

The new century opened with two contributions from the field of history continuing the unveiling of Russia’s sexual past. The first issue of the journal Kritika: Explorations in Russian & Eurasian History in the winter of 2000 published Brian Baer’s review essay “The Other Russia: Re-Presenting the Gay Experience.” Baer’s focus is on three books published in the late 1990s dealing with Russian LGBT history and literature, none of which have yet been translated. The first is the 1997 anthology Liubov’ bez Granits: Antologia Shedevrov Mirovoi Literatury’ (Love without borders: an anthology of masterpieces from world literature], containing selected works of homoerotic fiction. The importance of this volume is its placement of Russian writers such as Esenin, Kharitonov, Ivenev and Lermontov in context with LGBT writers more familiar to Western European audiences such as Proust and Oscar Wilde. Bar notes that the emphasis in the collection is heavily weighted in favor of the male voice, with major women authors such as Sophia Parnok, Zinaida Gippius and Marina Tsvetaeva absent. 1998 saw the publication of K. K. Rotikov’s ‘Drugoi Peterburg’ (The Other Petersburg). Done in the form of a guide to the city, this is the first-ever attempt to portray the interwoven LGBT past of St. Petersburg within its urban geography. The third book reviewed by Baer is a second work by sociologist Igor Kon’, Lunnyi Svet na Zare: Liki i Maski Odnopoloi Liubvi’ [Moonlight at dawn: faces and masks of same-sex love), first published in 1998 and reissued in 2002. It is significant as the first volume of scholarship on homosexuality ever published in Russia and its title is a reference to a 1911 title by Vasili Rozanov’s People of the Moonlight. Kon’s volume is arranged in three sections covering theories on the origins of homosexuality, homosexuality as constructed in a range of cultures and historical periods, and a review of modern sociological and psychological scholarship on gay and lesbian culture. One particularly valuable feature of the book is Kon’s provision of Russian equivalents for Western terms used to discuss homosexuality.

In 2002, Gay Life in the Former USSR: Fraternity Without Community by sociologist Daniel Schluter appeared from Routledge, although readers should be aware that the work is based on research done in Russia during the period 1990-1991. His aim in writing this work was “to put …descriptive information…about the Soviet gay and lesbian subculture into an analytical framework that distinguishes fraternal social institutions from communal ones by assessing the differences between them in the degree of their institutionalization.” (Schluter 2002: 7) The institutional settings for LGBT life in Russia examined are individual, societal and legal, with the first noted as “sufficient only for promoting the sense among Soviet homosexuals that they are a distinct ‘people’…not enough to inspire their coordinated socio-political action or.. their public self-identification as homosexuals,” (Schluter 2002: 7) Taken together, the societal context of bureaucracy, legal restraint, demographic patterns and geographic locations where gay and lesbian social life was possible did not allow for the formation of a “ gay community “ in the sense used in Western gay life. Schluter cautions that , “ since the general economic, political, societal and cultural conditions in…the former Soviet Union have generally not developed well enough for even the organizations of “mainstream “ social groups to function effectively, …those of the homosexual minority are not likely to materialize-or at least to be very successful- in the near future.” (Schluter 2002: 8) Readers may find it useful to compare Schluter’s conclusions about individual gay and lesbian life with the accounts in David Tuller’s Cracks in the Iron Closet: Travels in Gay & Lesbian Russia, as part of his time in post-Gorbachev Russia overlaps with Schluter’s visit there.

In January 2003, another short piece by Daniel Healey appeared in the journal History Compass, asking “What Can We Learn From the History of Homosexuality in Russia?” His response is a clear and valuable assessment of the ways homosexuality was thought of in Russia (in both imperial and Soviet times) and how the perception of Russia as a nation essentially innocent of such behaviors (as contrasted with the civilization of Western Europe and the perceived tolerance of same-sex practices in Central Asia) shaped reactions to them. It provides valuable context for much of the Russian writing on same-gender love and sexuality and the assumptions about its nature and origins reflected in it.

Given the significance of the writings and career of Igor Kon (who died in 2011) it is unfortunate that more of his works have not been widely translated from Russian. An excellent summary of three of his books published in Moscow between 1999 and 2003 (including Lunnyi Svet Na Zare: Liki i Maski Odnopoloi Liubvi’ [Moonlight at dawn: faces and masks of same-sex love) was provided in 2005 by Brian James Baer in his article for the Journal of Homosexuality “Igor Kon: The Making of a Russian Sexologist.“ It was followed in 2006 by Luc Beaudoin’s essay “Raising a Pink Flag: The Reconstruction of Russian Gay Identity in the Shadow of Russian Nationalism” in the collection Gender and National Identity in Twentieth-Century Russian Culture edited by Helena Goscilo and Andrea Lanoux. Beaudoin examines both the aesthetic constructions of sexuality and homosexuality created in and after the years of the Silver Age and their rediscovery and role in the definition of a gay identity to both LGBT people and mainstream Russian heterosexual society. 2007 saw the republication of Mikhail Kuzmin’s novel Wings in London, the first single edition of this important work in English since the 1972 collection from Ardis in Ann Arbor Michigan Wings: Prose and Poetry translated by Neil Granoien and Michael Green. Writing on the question of social identity for LGBT people in the new post-Soviet Russian world discussed by Beaudoin in 2006 continued with the publication in 2008 in Germany of Mikhail Nemtsev’s  How Did A Sexual Minorities Movement Emerge in Post-Soviet Russia?: An Essay. Based on his master’s dissertation in gender studies, this short book provides a thoughtful social history of the formation and dynamics of a movement for sexual minority rights in Russia in the 1989-1990 period considered within the identity politics of claiming a non-normative sexual orientation and a subsequent retreat from public activism. Notable in his research is work with primary print sources (including the private collection held by Igor Kon) and interviews with thirteen former members of the movement in Moscow and St.

How Did A Sexual Minorities Movement Emerge in Post-Soviet Russia?: An Essay. Based on his master’s dissertation in gender studies, this short book provides a thoughtful social history of the formation and dynamics of a movement for sexual minority rights in Russia in the 1989-1990 period considered within the identity politics of claiming a non-normative sexual orientation and a subsequent retreat from public activism. Notable in his research is work with primary print sources (including the private collection held by Igor Kon) and interviews with thirteen former members of the movement in Moscow and St.  Petersburg. And in 2009, Brian James Baer’s Other Russias : Homosexuality and the Crisis of Post-Soviet Identity explored” the often extravagant discourse on the subject that has been generated from the late 1980s through Vladimir Putin’s presidency…that may not only influence the ways in which homosexual-identified men and women…imagine themselves and construct their identities but also say something about the ways Russians in general-and Russian men in particular-imagine their post-Soviet identity, their cultural predicament.” (Baer 2009: 3)

Petersburg. And in 2009, Brian James Baer’s Other Russias : Homosexuality and the Crisis of Post-Soviet Identity explored” the often extravagant discourse on the subject that has been generated from the late 1980s through Vladimir Putin’s presidency…that may not only influence the ways in which homosexual-identified men and women…imagine themselves and construct their identities but also say something about the ways Russians in general-and Russian men in particular-imagine their post-Soviet identity, their cultural predicament.” (Baer 2009: 3)

The current decade has witnessed both the continuation of the established trends in scholarship on LGBT Russia and the expansion of the subject to fields as diverse as political science, film and music. In 2010, Hannah Dee’s The Red in the Rainbow : Sexuality, Socialism  and LGBT Liberation was published in London, and contains a chapter comparing the cases of gay and lesbian people in Germany and Russia within each nation’s crafting of a socialist state. Three years later, the collection From

and LGBT Liberation was published in London, and contains a chapter comparing the cases of gay and lesbian people in Germany and Russia within each nation’s crafting of a socialist state. Three years later, the collection From  Wrongs to Gay Rights: Cruelty and Change for LGBT People in An Uncertain World. Some of the contents of this book first appeared as posts on the Erasing 76 Crimes blog ( https://76crimes.com/ ) Edited by journalist and blog founder Colin Stewart, it includes a chapter on ” Russia : Time Line of Gay Rights and Gay Repression “ covering the period from 1993 to January 2013. Many of the entries in the timeline record the passage of local legislation prohibiting “gay propaganda” in venues where children might be present and one notes the court decision in Moscow upholding the city’s decision to ban gay pride parades for the next 100 years.

Wrongs to Gay Rights: Cruelty and Change for LGBT People in An Uncertain World. Some of the contents of this book first appeared as posts on the Erasing 76 Crimes blog ( https://76crimes.com/ ) Edited by journalist and blog founder Colin Stewart, it includes a chapter on ” Russia : Time Line of Gay Rights and Gay Repression “ covering the period from 1993 to January 2013. Many of the entries in the timeline record the passage of local legislation prohibiting “gay propaganda” in venues where children might be present and one notes the court decision in Moscow upholding the city’s decision to ban gay pride parades for the next 100 years.

The topic of how to achieve and maintain an LGBT identity under socialism treated in The Red in The Rainbow received expanded coverage in the eleven essays that comprise the 2013 anthology Queer Visibility in Post-Socialist Cultures. While focused chiefly on the nations of the former East European bloc, it also includes chapters by Kevin Moss speaking of the “Straight Eye for the Queer Guy: Gay Male Visibility in Post-Soviet Russian Films “and Brian Baer’s “Now You See It: Gay (In) Visibility and the Performance of Post-Soviet Identity.”

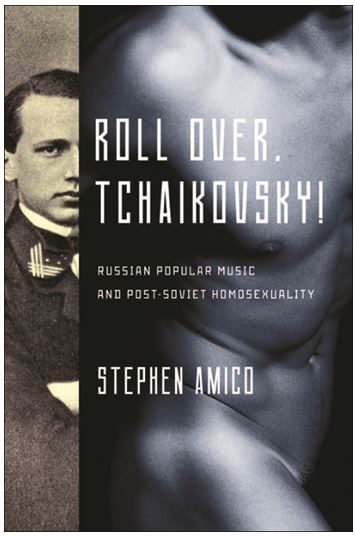

A second anthology, Queer Presences and Absences, published by Palgrave Macmillan in 2013,  expanded the body of information available on the lives of Russian lesbians outside the institutional contexts of law and psychiatry with Francesca Stella’s essay “Lesbian Lives and Real Existing Socialism in Late Soviet Russia “based on interviews with twenty-four women. 2013 is also notable for the appearance of a documentary film done with the assistance of Amnesty International, They Hate Me In Vain: LGBT Christians in today’s Russia. Slightly more than an hour in length, this is the first such film to be created on this subject. The trailer for it can be viewed online at https://invanomiodiano.wordpress.com/english/. Another online resource from 2014 is the complete text of Tanya Cooper’s report License to Harm: Violence and Harassment Against LGBT People and Activists in Russia issued by the Human Rights Watch. 2014 also saw the publication of Brian Baer’s entry on “Russian Gay and Lesbian Literature“ in The Cambridge History of Gay and Lesbian Literature and Stephen Amico’s groundbreaking Roll Over, Tchaikovsky! Russian

expanded the body of information available on the lives of Russian lesbians outside the institutional contexts of law and psychiatry with Francesca Stella’s essay “Lesbian Lives and Real Existing Socialism in Late Soviet Russia “based on interviews with twenty-four women. 2013 is also notable for the appearance of a documentary film done with the assistance of Amnesty International, They Hate Me In Vain: LGBT Christians in today’s Russia. Slightly more than an hour in length, this is the first such film to be created on this subject. The trailer for it can be viewed online at https://invanomiodiano.wordpress.com/english/. Another online resource from 2014 is the complete text of Tanya Cooper’s report License to Harm: Violence and Harassment Against LGBT People and Activists in Russia issued by the Human Rights Watch. 2014 also saw the publication of Brian Baer’s entry on “Russian Gay and Lesbian Literature“ in The Cambridge History of Gay and Lesbian Literature and Stephen Amico’s groundbreaking Roll Over, Tchaikovsky! Russian  Popular Music and Post-Soviet Homosexuality from the University of Illinois Press New Perspectives on Gender in Music series. Using data from interviews in Moscow and Saint Petersburg, Amico’s study explores the complex forms of expression in and uses made of music lyrics and performances by both artists and audiences to articulate and shape a homosexual identity in contemporary Russia. The personal voice of an outsider encountering the realities of LGBT Russian life heard in David Tuller’s Cracks in the Iron Closet in 1996 returned in 2015 in Sonja Franeta’s account My Pink Road to Russia: Tales of Amazons, Peasants,

Popular Music and Post-Soviet Homosexuality from the University of Illinois Press New Perspectives on Gender in Music series. Using data from interviews in Moscow and Saint Petersburg, Amico’s study explores the complex forms of expression in and uses made of music lyrics and performances by both artists and audiences to articulate and shape a homosexual identity in contemporary Russia. The personal voice of an outsider encountering the realities of LGBT Russian life heard in David Tuller’s Cracks in the Iron Closet in 1996 returned in 2015 in Sonja Franeta’s account My Pink Road to Russia: Tales of Amazons, Peasants,  and Queers. The third section of text, “Journeys and Interviews in Russia,“ begins with her arrival in Leningrad in July 1991 for the first gay and lesbian film festival and follows with in-depth interviews and colorful stories of the women and men she met there and her travels to visit them in cities across the country including Novosibirsk, Krasnoyarsk, and Moscow. One of her more notable interviews is with a man who spent eighteen years in the gulag for being gay. And Dan Healey with his 2017 study Russian Homophobia from Stalin to Sochi brings the stream of historical writing on the environment faced by LGBT people in Russia up to the current government of Vladimir Putin.

and Queers. The third section of text, “Journeys and Interviews in Russia,“ begins with her arrival in Leningrad in July 1991 for the first gay and lesbian film festival and follows with in-depth interviews and colorful stories of the women and men she met there and her travels to visit them in cities across the country including Novosibirsk, Krasnoyarsk, and Moscow. One of her more notable interviews is with a man who spent eighteen years in the gulag for being gay. And Dan Healey with his 2017 study Russian Homophobia from Stalin to Sochi brings the stream of historical writing on the environment faced by LGBT people in Russia up to the current government of Vladimir Putin.

The literature on LGBT lives as shaped and lived out within and outside uniquely Russian political, legal, and social environments from the days of the tsars to the twenty-first century reveals a complex and evolving story of persistence, courage, and a vital and enduring presence.

References

Amico, Stephen. Roll Over, Tchaikovsky! Russian Popular Music and Post-Soviet Homosexuality. Urbana, Illinois: University of Illinois Press, 2014.

Baer, Brian James. “The Other Russia: Re-Presenting the Gay Experience.” Kritika: Explorations in Russian & Eurasian History. 1(1) Winter 2000: 183-194.

Baer, Brian James. “Igor Kon: The Making of a Russian Sexologist.” Journal of Homosexuality 49.2 (2005): 157-163.

Baer, Brian James. Other Russias: Homosexuality and the Crisis of Post-Soviet Identity. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009.

Baer, Brian James. “Now You See It: Gay (In) Visibility and the Performance of Post-Soviet Identity.” in Queer visibility in post-socialist cultures edited by Nárcisz Fejes and Andrea P Balogh. Bristol; Chicago: Intellect, 2013: 35-56.

Baer, Brian James. “Russian Gay and Lesbian Literature“ in The Cambridge History of Gay and Lesbian Literature. Cambridge, England; Cambridge UP; 2014: 421-437.

Beaudoin, Luc. “Raising a Pink Flag: The Reconstruction of Russian Gay Identity in the Shadow of Russian Nationalism“ in Gender and National Identity in Twentieth-Century Russian Culture edited by Helena Goscilo and Andrea Lanoux. DeKalb, IL: Northern Illinois UP; 2006 : 224-240.

Burgin, Diana Lewis. “Sophia Parnok and the writing of a lesbian poet’s life.” Slavic Review 51 (2) (Summer 1992): 214-231.

Burgin, Diana Lewis. Sophia Parnok: The Life and Work of Russia’s Sappho. New York: New York U. Pr., 1994.

The Cambridge History of Gay and Lesbian Literature. Cambridge, England; Cambridge UP, 2014.

The Columbia Anthology of Gay Literature: Readings from Western Antiquity to the Present Day, edited by Byrne R.S. Fone. New York: Columbia University Press, 1998.

Cooper, Tanya. License to Harm: Violence and Harassment against LGBT People and Activists in Russia. Human Rights Watch, 2014. https://www.hrw.org/report/2014/12/15/license-harm/violence-and-harassment-against-lgbt-people-and-activists-russia

Dee, Hannah. The Red in the Rainbow: Sexuality, Socialism and LGBT Liberation. London: Bookmarks Publications, 2010.

Engelstein, Laura. “Soviet Policy toward Male Homosexuality: Its Origins and Historical Roots.” Journal of Homosexuality 29 (2-3) (1995): 155-178.

Erasing 76 Crimes (https://76crimes.com/ )

“Erotic Revolutionaries: Russian Literature (1836-1922) in The Columbia Anthology of Gay Literature: Readings from Western Antiquity to the Present Day, edited by Byrne R.S. Fone. New York: Columbia University Press, 1998: 457-468.

Essig, Laurie. Queer in Russia: a story of sex, self, and the other. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1999.

Franeta, Sonja. My Pink Road to Russia: Tales of Amazons, Peasants, and Queers. Oakland, California: Dacha Books, 2015.

From Wrongs to Gay Rights: Cruelty and Change for LGBT People in an Uncertain World. Colin Stewart, editor. Laguna Niguel, California: P.C. Haddiwiggle Publishing Company, 2013.

Gareev, Zufar, et.al. “Gay’s the Word in Moscow“ Index on Censorship: The Magazine for Free Speech 24(1) (January 1995)

Gay roots: twenty years of Gay sunshine: an anthology of gay history, sex, politics, and culture, edited by Winston Leyland. San Francisco: Gay Sunshine Press, c1991-1993. 2 vols.

Gender and National Identity in Twentieth-Century Russian Culture, edited by Helena Goscilo and Andrea Lanoux. DeKalb, IL; Northern Illinois UP, 2006.

Gessen, Masha. The Rights of Lesbians and Gay Men in the Russian Federation : An International Gay and Lesbian Human Rights Commission Report. San Francisco, California: IGLHRC, 1994.

Gessen, Masha. “Sex in the Media and the Birth of the Sex Media in Russia.” Genders.22 (1995) : 197-228.

Healey, Dan. “The Russian Revolution and the Decriminalisation of Homosexuality.” Revolutionary Russia 6 (1) ( 1993) : 26-54.

Healey, Daniel. Homosexual desire in revolutionary Russia: Public and hidden transcripts, 1917-1941. Ph.D thesis, University of Toronto, 1998.

Healey, Dan. Homosexual desire in Revolutionary Russia: the regulation of sexual and gender dissent. Chicago : University of Chicago Press, 2001.

Healey, Dan. “What Can We Learn from the History of Homosexuality in Russia? “ History Compass. 1 (1) ( 2003 ) : 1-6.

Healey, Dan. Russian Homophobia from Stalin to Sochi. London ; New York, New York : Bloomsbury Academic, an imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc, 2018.

Hidden From History: Reclaiming the Gay and Lesbian Past, edited by Martin B. Duberman, Martha Vicinus and George Chauncey. New York: Meridian, 1990, ©1989.

Karlinsky, Simon. “Russia’s Gay Literature and History.” Gay Sunshine 29/30, 1976: 1-7

Karlinsky, Simon. “Death and Resurrection of Mikhail Kuzmin.” Slavic Review 38 (1) (1979) : 92-96.

Karlinsky, Simon “Gay Life Before the Soviets: Revisionism Revised “ The ADVOCATE 339 ( 9 April 1982 ) : 31-34.

Karlinsky, Simon. “Russia’s Gay Literature and Culture: The Impact of the October Revolution“ in Hidden From History : Reclaiming the Gay and Lesbian Past edited by Martin B. Duberman, Martha Vicinus and George Chauncey. New York: Meridian,1990, ©1989: 347-364.

Karlinsky, Simon. “Russia’s Gay History and Literature from the Eleventh to the Twentieth Centuries” in Gay Roots : Twenty Years of Gay Sunshine : An Anthology of Gay History, Sex, Politics, and Culture edited by Winston Leyland. San Francisco : Gay Sunshine Press, c1991-1993: 81-104.

Kepner, James. “Powerful Film Delves Into Life of Famed Composer.” The ADVOCATE 53 ( February 17-March 1, 1971) : 18.

Kon, Igor S. The Sexual Revolution in Russia: from the Age of the Czars to Today. New York: Free Press, 1995.

Kuzmin, Mikhail. Wings: Prose and Poetry. Ann Arbor: Ardis, 1972.

Kuzmin, Mikhail. “The Dangerous Precaution“ in Lovesick: Modernist Plays of Same-Sex Love, 1894-1925 compiled by] Laurence Senelick. London; Routledge, 1999 : 103-116.

Kuzmin, Mikhail. Wings. London: Hesperus, 2007.

Lovesick: Modernist Plays of Same-Sex Love, 1894-1925 compiled by] Laurence Senelick. London ; Routledge, 1999.

Malmstad, John E. and Nikolay Bogomolov. Mikhail Kuzmin: A Life in Art. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard U. Pr., 1999.

Moss, Kevin. “Straight Eye for the Queer Guy: Gay Male Visibility in Post-Soviet Russian Films.“ in Queer Visibility in Post-Socialist Cultures edited by Nárcisz Fejes and Andrea P. Balogh. Bristol ; Chicago: Intellect, 2013: 197-220.

Nemtsev, Mikhail. How Did A Sexual Minorities Movement Emerge in Post-Soviet Russia?: An Essay. Saarbrücken : VDM, Verlag Dr. Müller, 2008.

Out of the Blue: Russia’s Hidden Gay Literature: An Anthology edited by Kevin Moss. San Francisco, California: Gay Sunshine Press, 1996.

Queer Presences and Absences edited by Yvette Taylor and Michelle Addison. Houndmills: Basingstoke, Hampshire ; New York : Palgrave Macmillan, 2013.

Queer visibility in post-socialist cultures edited by Nárcisz Fejes and Andrea P. Balogh. Bristol ; Chicago: Intellect, 2013.

Schluter, Daniel P. Gay Life in the Former USSR: Fraternity Without Community. New York: Routledge, 2002.

Shatalov, Alexander. “Glagol: Russia’s First Gay Publishing House Flourishing.” Glas: New Russian Writing 8 (1994): 194-200.

Stella, Francesca. “Lesbian lives and real existing socialism in late Soviet Russia.” In Queer presences and absences edited by Yvette Taylor and Michelle Addison. Houndmills : Basingstoke, Hampshire ; New York : Palgrave Macmillan, 2013: 50-68.

Tema. Moskva: Tema, 1990–1993.

They Hate Me In Vain: LGBT Christians in Today’s Russia ; the first film to address the reality of LGBT Christians in Russia. Documentary by Yulia Matsiy with the patronage of Amnesty International. https://invanomiodiano.wordpress.com/english/ (trailer)

Tuller, David. Cracks In the Iron Closet: Travels To Gay & Lesbian Russia. Boston : Faber and Faber, 1996.

Copyright R. Ridinger 2018.

… [Trackback]

[…] Read More Infos here: glbtrt.ala.org/reviews/off-the-shelf-23-around-the-samovar-tracking-lgbt-russian-histories/ […]